Limoges quickly became the centre of porcelain production following the discovery of kaolin in the Limousin region in 1768. Numerous large factories sprang up in the city and provided work for the local population – men, women and, as old postcards show, even children. Production reached its peak at the beginning of the 20th century: 55 factories with 130 kilns employed around 12,000 workers. Today, a dozen factories are still active in Limoges. The best places to explore the porcelain worlds of the past and present are the Museée National Adrien Dubouché, the Museum Four des Casseaux, the Atelier Arquié and the Bernardaud factory.

Porcelain for the king

In the 18th century, a race broke out, fuelled by Europe’s royal houses. At last, they wanted to produce fine porcelain in their own country instead of buying it in large quantities from China at great expense. In 1712, the Jesuit missionary François-Xavier d’Entrecolles discovered through research – an early form of industrial espionage – that the finest hard porcelain required a special white earth. The Chinese called it kaolin, “high hill”, after the first place where porcelain clay was found in China. With this knowledge, the search for kaolin began in France. The small kingdom of Saxony was already further ahead: kaolin was mined in the Ore Mountains near Aue, and the Meissen manufactory produced its first hard porcelain from 1710. The French royal family came under pressure – France’s own porcelain production finally had to start.

Isabeau Darnet and the white gold

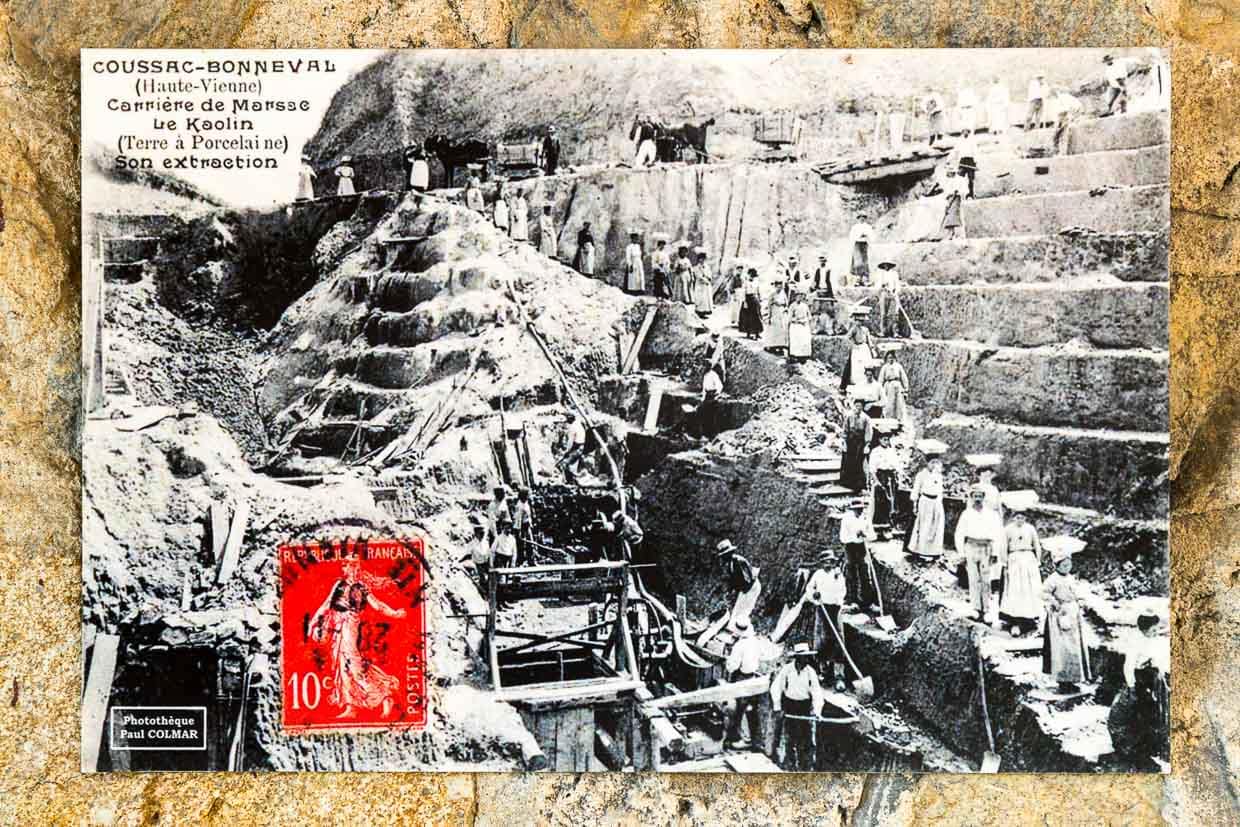

Isabeau Darnet from Saint-Yrieix near Limoges, the wife of the local surgeon, ended the long search for the coveted material. For her household, she used a fine, white earth that was remarkably soft. Her husband suspected that this substance might be valuable and sent samples to his friends in the trade. The pharmacist Marc-Hilaire Villaris from Bordeaux recognised kaolin in it – the indispensable raw material for porcelain production. The discovery became known and the area passed to King Louis XV. With state support, targeted mining began. Jean-Baptiste Darnet received a good salary to manage the site in Saint-Yrieix. At last, the production of flawless white porcelain for the French court could begin. Isabeau Darnet, later mentioned only in passing, probably benefited from her husband’s salary. Her discovery changed Saint-Yrieix and the Limoges region for two centuries: quarries were set up in the old chestnut forests and white spoil heaps accentuated the birch-covered heathland. The discovery of kaolin marked the beginning of Limoges’ rise to become an important porcelain centre.

Limoges – Meissen – Copenhagen

Like Meissen porcelain in Germany and Royal Copenhagen in Denmark, Limoges porcelain stands for the highest quality: fine, translucent, rich in detail. It is considered a symbol of French tableware culture and has been part of the intangible cultural heritage since 2008. Today, many consider Limoges to be synonymous with French porcelain. It is in demand worldwide, is collected, bought and often used in everyday life. The city combines industrial tradition with creative craftsmanship. For French and international porcelain lovers, it epitomises the more accessible, democratic part of porcelain culture – in contrast to royal manufactories such as Sèvres near Paris.

The revolution boosts production

In France, hard porcelain production gained momentum at the same time as the French Revolution disempowered the nobility – once the main clientele of the precious porcelain. Limoges gained a reputation as a city with a democratic and accessible porcelain culture, while the Sèvres manufactory near Paris is still synonymous with royal splendour and expensive unique pieces. The revolution from 1789 onwards democratised brands and production methods: Instead of representing the royal elite, they now embodied the values of the bourgeoisie and the republic. Working conditions in the factories remained harsh. However, men who learnt demanding skilled trades were able to achieve social advancement. Women were denied access to these professions for a long time.

Royal mothballs

After the abolition of the monarchy and the upheavals of the revolution, terms such as royal disappeared from company names. Factories were renamed, acquired new owners and henceforth bore designations such as national factory or the names of their owners. The porcelain factory founded by François Alluaud in 1797, initially known as Porcelaines Alluaud, changed its name several times over the years: from CFH (Charles Field Haviland) to GDM (Gérard Dufraisseix and Morel) to GDA (Gérard Dufraisseix and Abbott). It was not until 1989 that the company decided in favour of the name Royal Limoges. It wanted to emphasise the connection to the French monarchy and highlight the heritage of the manufactory. A staircase joke of history: What disappeared in 1789 in the name of the Revolution returned 200 years later as a successful marketing strategy.

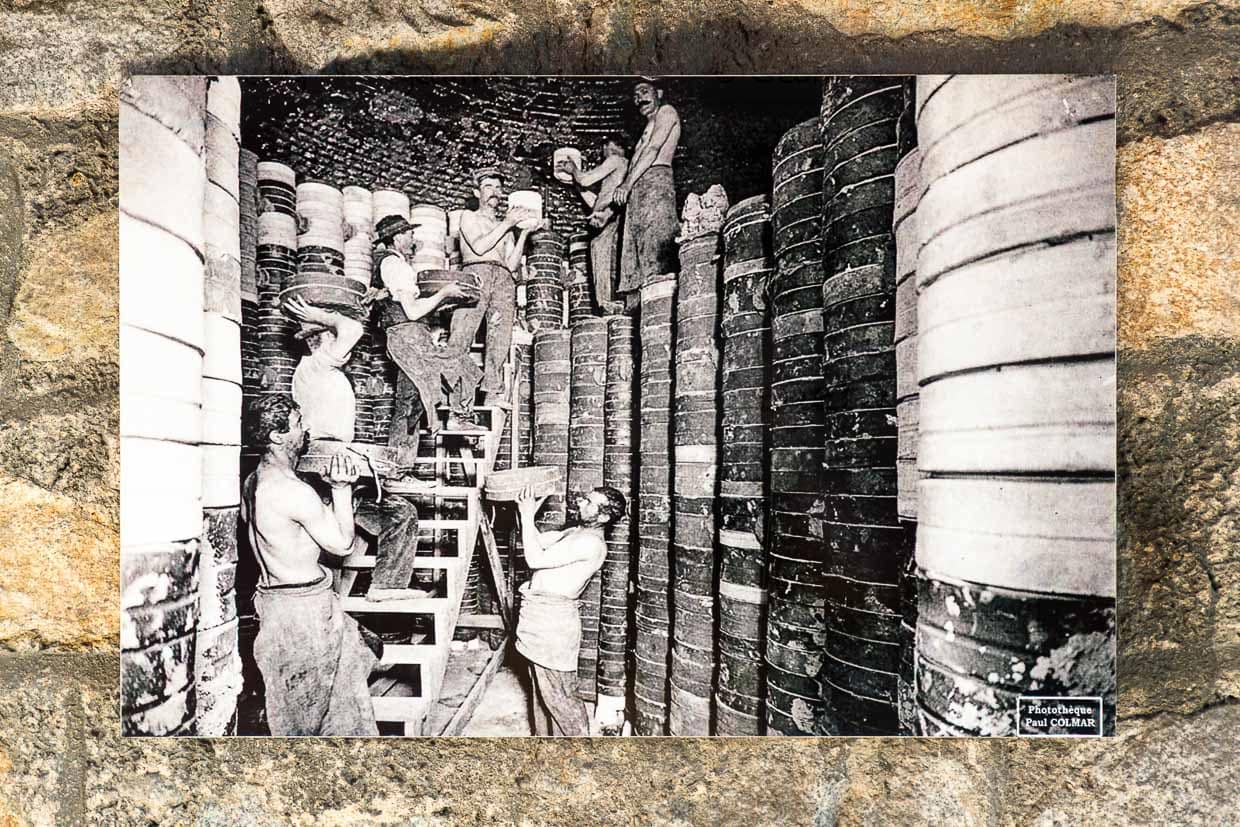

Hot tip: Museum Four des Casseaux

From 1904 to 1957, the Four des Casseaux was the central kiln of one of the most important porcelain factories in the region, Gérard-Dufraisseix-Abbott. It has been a listed building since 1987 and forms the centrepiece of an exceptional exhibition concept. The Four des Casseaux Museum shows the technical, industrial and social development of porcelain production. A collection of postcards and photos, supplemented by historical documents, illustrates the factory work around the kiln. The exhibition organisers owe this collection to the photographer and collector Paul Colmar. Now over 85 years old, he began collecting postcards at the age of 16, capturing the working life of the time. A visit to the Four des Casseaux Museum is doubly worthwhile: it is located close to the Vienne, making it ideal for combining a tour with a walk along the riverbank. You can enjoy one of the most beautiful views of Limoges with the old Saint-Étienne stone bridge.

The interior of the Four des Casseaux can also be viewed in the museum. The kiln can hold up to 15,000 pieces of porcelain per firing. Production took ten days: the kiln was loaded for two days, after which it reached 900 degrees in the upper section and 1,400 degrees in the lower section. The fire burned for three days, the kiln cooled down for another three, and finally it was emptied in two days. The Four des Casseaux Museum is open Monday to Saturday, admission is very reasonable at 4.50 euros and a guided tour is available for 9 euros if you book in advance.

Musée National Adrien Dubouché

The Musée National Adrien Dubouché is considered the most important museum for porcelain art and is home to the world’s largest public collection with over 18,000 pieces. A tour takes you chronologically through the history of ceramics – from antiquity to the present day, from porcelain techniques to contemporary works and international ceramic art. Adrien Dubouché, the son of a cloth merchant and a committed patron of the arts, took over the management of the museum in 1865. With generous donations and the acquisition of important collections, he considerably expanded the exhibition. The museum was given his name during his lifetime.

Ateliers Arquié

In the Ateliers Arquié, visitors can experience modern porcelain production in Limoges. The workshop combines traditional craftsmanship with contemporary shapes, colours and techniques. For some years now, it has been located in a former spinning and weaving mill on the banks of the Vienne. Large-format graffiti by regional artists adorn the walls. Founded in 1996, the Kunstporzellanwerkstatt specialises in individually designed and artistic porcelain objects.

The workshop and factory outlet are united under one roof. Around 15 artists work together with the studio. Pharmaceutical porcelain used to be produced here. Today, visitors can look over the shoulders of the craftsmen and experience the individual steps – from moulding and casting to decoration – at first hand. Guided tours of the Ateliers Arquié with demonstrations of the work steps take place several times a week.

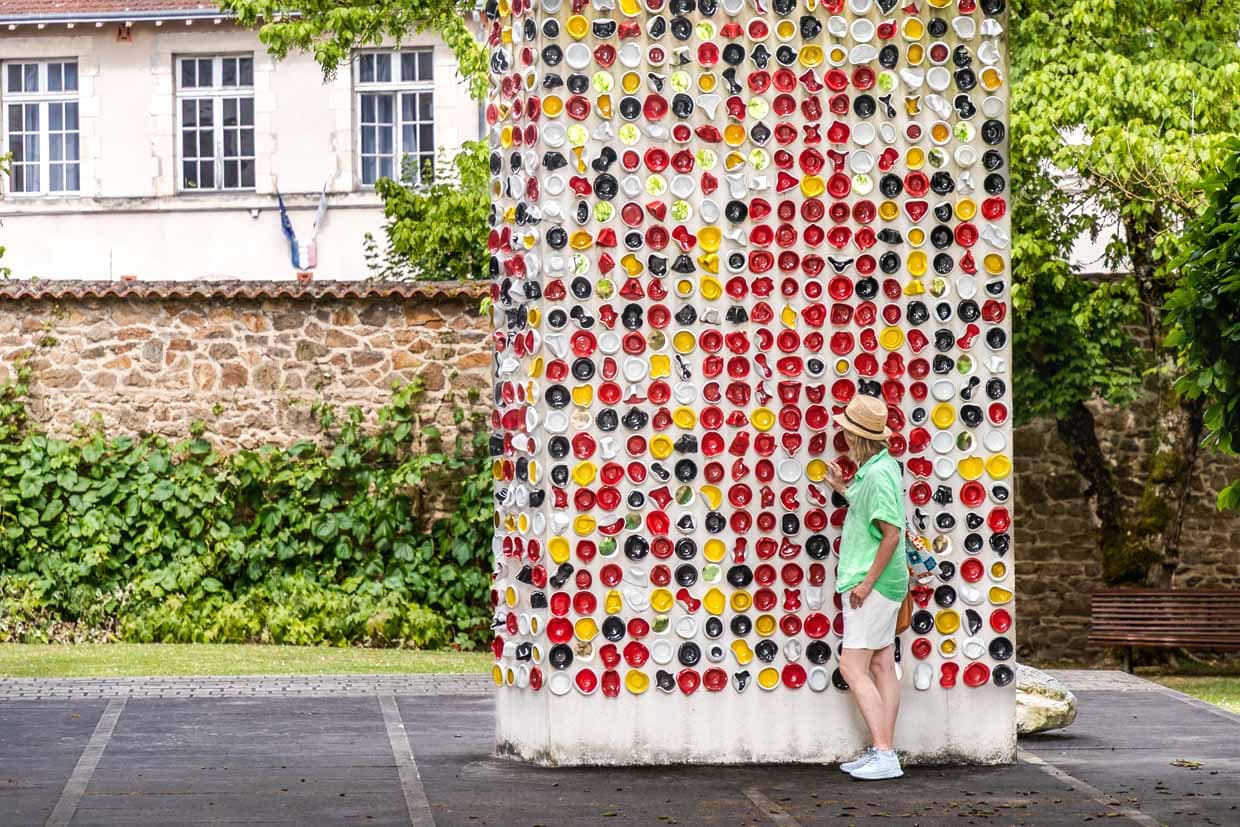

The atelier bears the French label Entreprise du Patrimoine Vivant (Living Heritage Company), which stands for exceptional traditional expertise. Together with the designer Marc Aurel, a series of urban seating furniture made of porcelain was developed, which today stands in front of Limoges town hall and can be seen in the Musée Adrien Dubouché.

Highlights in Nouvelle-Aquitaine

The Charente winds its way through the French region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine for 380 kilometres. Its course leads from the mountainous headwaters over rolling hills and vineyards to the maritime floodplains at the estuary. From Angoulême, the French capital of comics, the river is navigable all the way to the Atlantic at Rochefort. It was once the main transport route for cognac production. Today, cognac houses and winegrowers invite you to take part in spirit tourism, while cycle paths such as the Flow Vélo take you past picturesque villages, old stone bridges, a rare floating ferry, water mills, castles and the historic centre of Angoulême. The Charente is still an insider tip, as it is one of the most unspoilt river landscapes in France: hardly any mass tourism, but plenty of nature, tranquillity and enjoyment. The small island of Aix was once a bulwark to protect the Charente estuary from enemy fleets and is now a popular destination for a day trip to the sea. There is also plenty to discover in Nouvelle-Aquitaine away from the Charente. For example, some skewered plate art made us think outside the box once again. The city of Poitiers, halfway between Paris and Bordeaux, was the centre of power in the Middle Ages and offers immersive cinema at the Futuroscope leisure park. The city of Limoges is famous for its French porcelain, and a tour of the city provides an insight into the art of porcelain making. There are also great museums dedicated to the history of porcelain art . The journey continues to the Creuse and Berry region. It is the home of the writer George Sand and the cradle of tapestry in France. In A Carpet for George Sand, the two themes are linked. The Cité internationale de la Tapisserie in Aubusson shows that carpets are not the dusty art of bygone days.

The research trip was supported by Nouvelle-Aquitaine Tourism and Limoges Tourism