The Swiss border and trading city of Basel is home to Switzerland’s oldest university, 46 museums and has served as a refuge for many a maverick thinker. Erasmus of Rotterdam worked here during the transition from medieval to modern times, and Friedrich Nietzsche was appointed professor of ancient Greek philology at the university in 1869 at the age of 25. 150 years later, a special cultural history exhibition at the Historisches Museum Basel presents the work and impact of the most radical philosopher of modernity.

No other bridge crossed the Rhine between the North Sea and the Alps until the end of the Middle Ages. In 1225, the construction of the Middle Bridge gave Basel a key role in Europe for the spread of goods and cultural values. Prosperity came to the city. At the Council of Basel in 1439, the only papal election outside Rome was held. The first university on Swiss territory was also founded in Basel.

Built in the Romanesque-Gothic style, Basel Cathedral initially functioned as an Episcopal church, but has been a Protestant Reformed house of worship since the Reformation. As a contemporary witness, the eminent scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam was shocked by the destruction of the iconoclasm and turned his back on Basel for the next six years and went to Freiburg. Nevertheless, as a Catholic clergyman, he was accorded such great respect in Reformed Basel that he was buried in the cathedral.

Basilisk fountain

Throughout the city there are fountains where drinking water gushes from the mouth of a basilisk figure. This mythical mythical creature was depicted after the Basel Council as the bearer of the Basel city coat of arms with the black bishop’s staff. Basilisks are considered to be a hybrid creature of a rooster, dragon and eagle, symbolizing sin, the devil or the Antichrist.

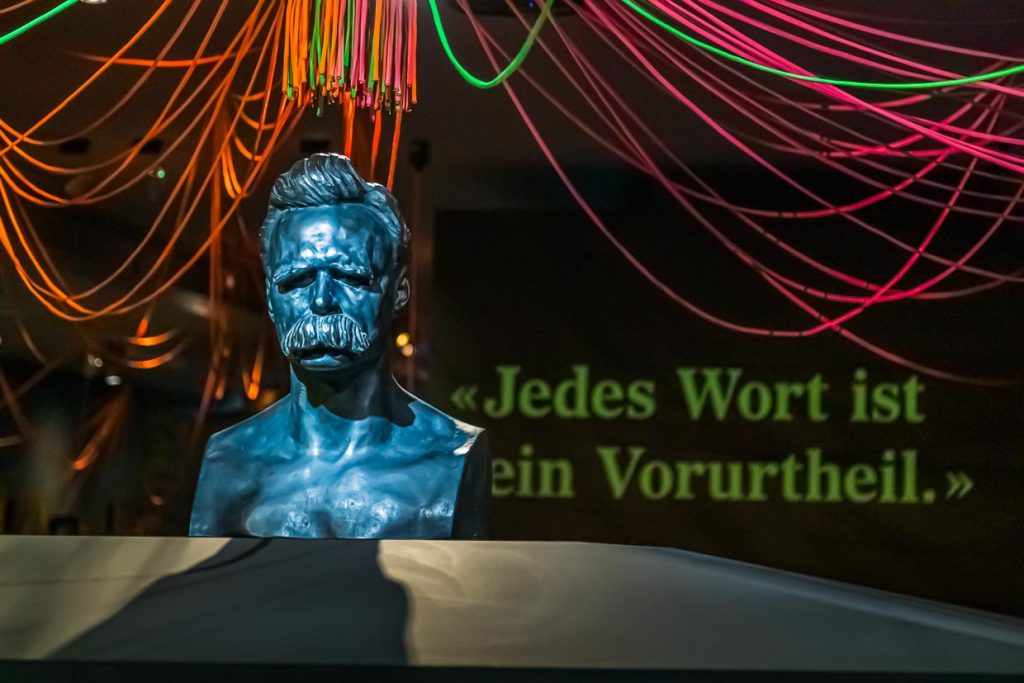

“Übermensch – Friedrich Nietzsche and the Consequences.”

The Basilisk could also be a symbolic figure for Friedrich Nitzsche, who began his professional career in Basel, as it upsets the established structure of time and space. In Antichrist, for example, Nitzsche wants to philosophize with a hammer and reevaluate old values.

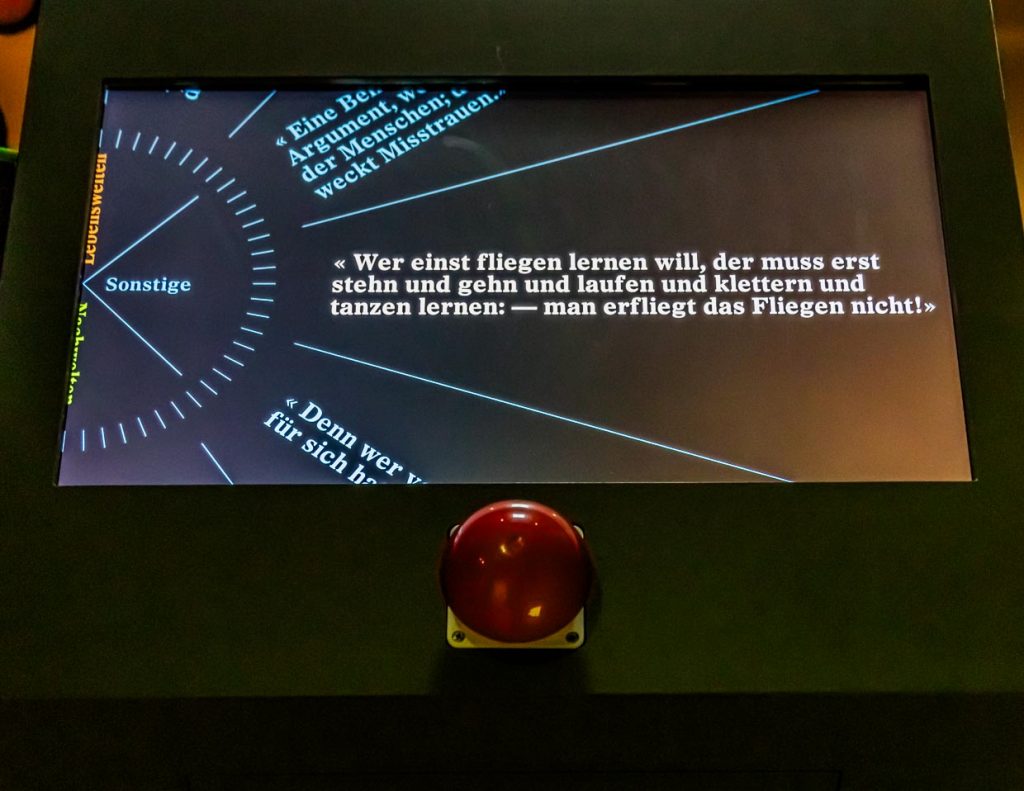

The Historical Museum brings Nietzsche’s world of thought to life in the Barfüsserkirche and presents his eventful life in an entertaining journey of discovery. His works offer witty quotations for every occasion and many word creations have passed into everyday language.

Nietzsche is not a philosopher and a poet on the side. He is both at the same time. His work offers room for interpretation in all directions. His sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche played an inglorious role. She presented her brother as a brand, with supernatural powers, and instrumentalized him, who had left his estate to her during his lifetime, for the support of National Socialist ideas. She skillfully combined his best-known identifying mark, the powerful mustache, with a military and tendentially violent character.

Nietzsche himself writes in the aphorism 381 of his Morgenröthe: “Thus the most gentle and cheapest man, if he has only a large mustache, can sit, as it were, in the shadow of the same …”. The Basel artist Alexander Zschockke not only created the official bust for the University of Basel, which depicts Nietzsche in the stylized pose of the free thinker. Privately, he wanted to overcome the post-fame staged by Nietzsche’s sister and look behind the omnipresent moustache. The sculpture The Young Nietzsche was created from the few youthful pictures preserved in the Nietzsche Archive in Weimar.

In the course of Nietzsche’s artistic and pop-cultural reception, the mustache seems to grow more and more over time. Visitors to the exhibition put themselves in the thinker’s place by waiting patiently with self-made mustaches for a photo in which they themselves are the center of attention.

One of two first prints of the famous group photo with lady (Lou von Salomé with whip, Paul Rée and Friedrich Nietzsche) can be seen in the exhibition. Because Lou von Salomé liked to show this photo around, Nietzsche broke with his friends. Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth saw the reputation of her brother as ascetic, which she had propagated, endangered by this. In the end, she successfully thwarted the plans of the three friends for a joint study visit.

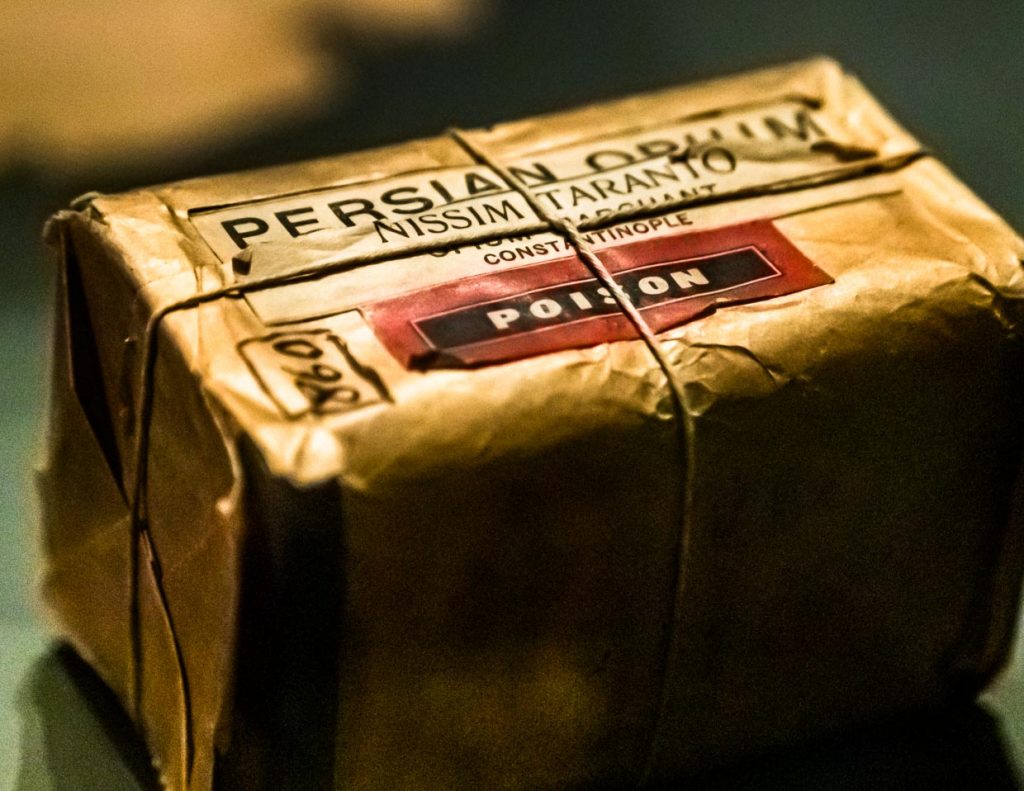

Throughout his life, Nietzsche suffered from migraines, semi-blindness, insomnia, and depressive moods. With Persian opium, a drug still permitted at that time, he at least tried to fight his insomnia.

Despite his health problems and his awkwardness in practical matters, Nietzsche traveled a lot. The small village of Sils Maria in the Engadine was inspiring for his philosophy of the eternal return of the same, and the high altitude at the same time alleviated the headache from which Nietzsche suffered almost everywhere else. More about Nietzsche’s retreat Sils Maria in the report about the Waldhaus Sils.

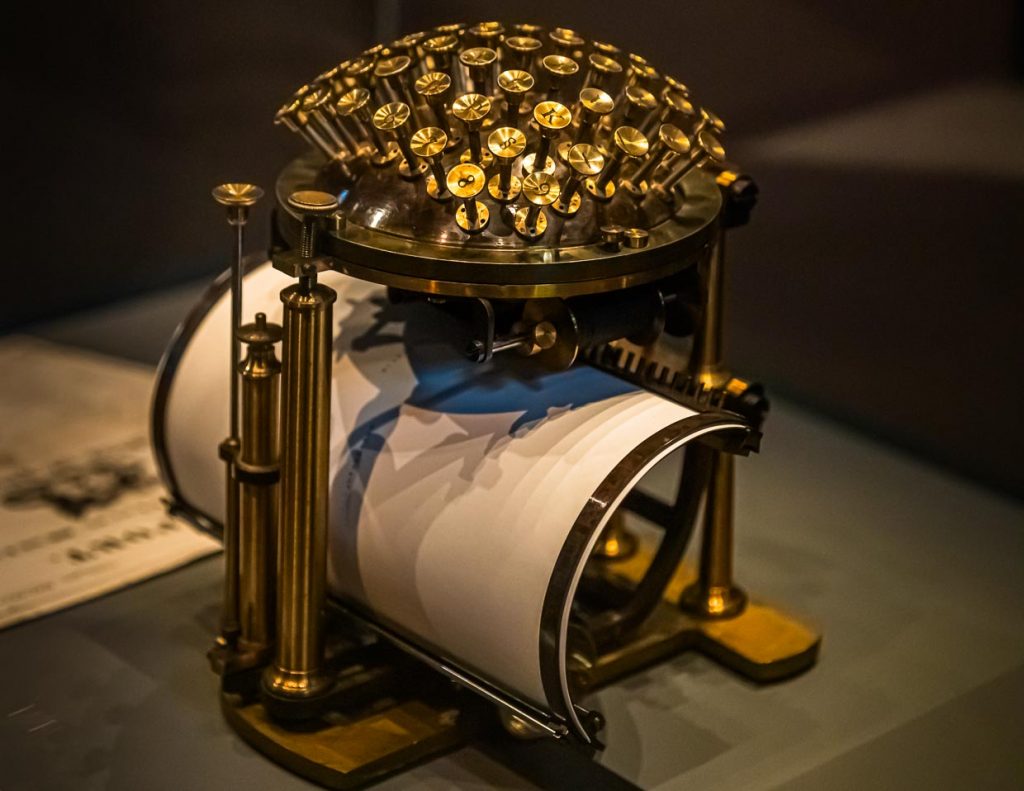

Writing was an essential part of Nietzsche’s life. Due to increasing visual impairment, however, Nietzsche was soon no longer able to make his own notes. He hoped that the writing ball he had just invented would solve his problems. His sister gave him the first mass-produced typewriter for Christmas in 1881.

The exhibition Übermensch – Friedrich Nietzsche and the Consequences in Historisches Museum Basel lasted from Oct. 16, 2019, to March 22, 2020. Such exhibitions rely on generous sponsorship, since the public budget in Basel is used only for museum operations. The Nietzsche exhibition was made possible thanks to the Res Ubique Foundation of Swiss banker and Nietzsche connoisseur Peter Buser.

The research trip was supported by Switzerland Tourism