After a long drive on the motorway, we come to a dirt track in the northern Black Forest. Our sat nav has led us to the Monhardter Wasserstube. But apart from the forest, a hint of smoke in the clear Black Forest air and the distant sound of a stream – nothing. No signs, no buildings, no people.

I call Martin Spreng, whose number we have noted down as a precaution. He picks up immediately and patiently describes the route: “Down the path, towards the water, then left along the stream. I’ll wait for you there.” His voice sounds amused – he is obviously used to visitors not finding the “Wasserstube” straight away.

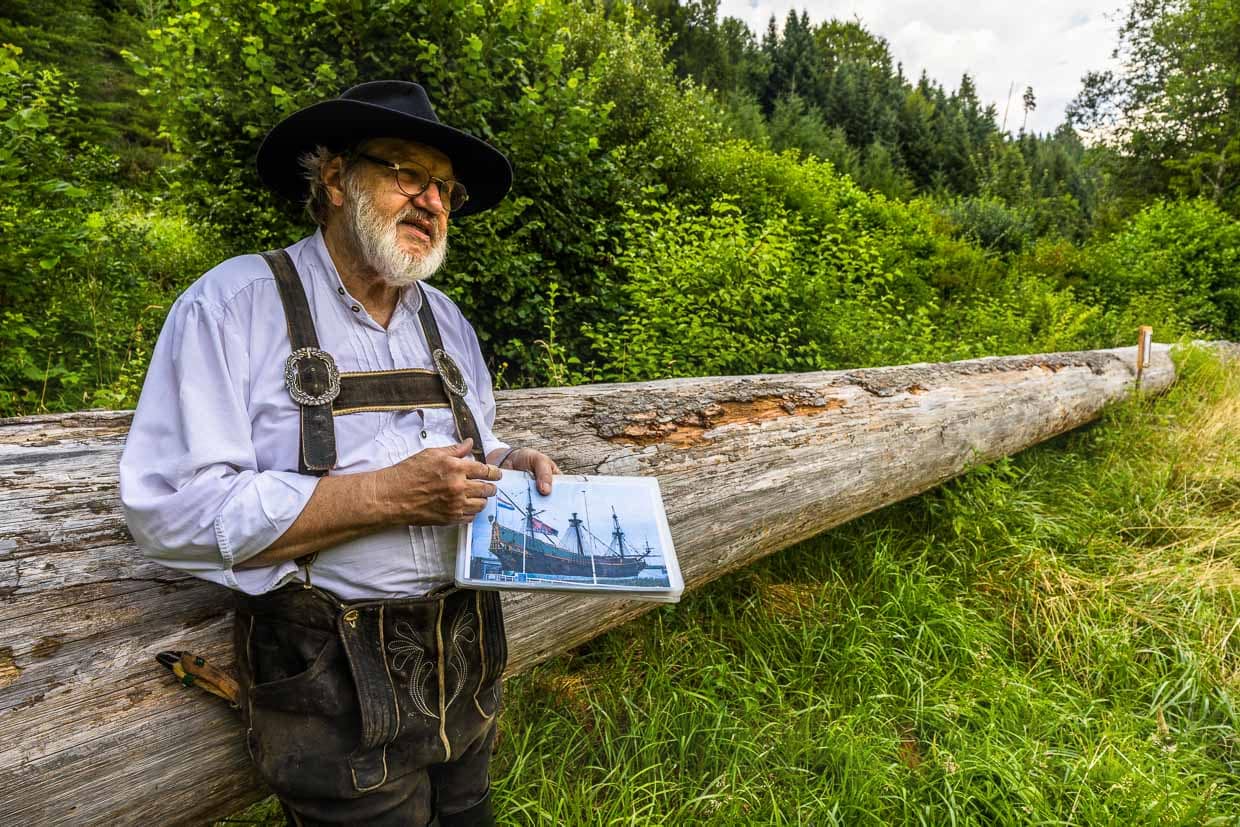

Five minutes later, we are standing in front of a structure that spans the stream: Chain winches, sluice gates, a shallow water area in front of it. Martin Spreng, chairman of the German Rafting Association, awaits us in his typical hip-high brimmed boots. What we experience over the next few hours is a journey back in time – to a world that disappeared only a century ago, but feels like it belongs to another millennium. A world in which rivers were the railway lines of Europe and wood was the oil of the day.

Amsterdam stands on Black Forest fir trees

The Dutch economic power of the 17th century owed much of its strength to the Black Forest fir. Amsterdam, built on marshy ground, rests on millions of wooden piles. The Royal Palace alone stands on 13,000 piles from the Black Forest. Rafting ensured the supply of timber and thus laid the foundations for the Dutch Golden Age.

Every year, workers cut tens of thousands of logs in the Black Forest and floated them along an 800-kilometre route across small rivers such as the Nagold to the Rhine. From there, large rafts transported the wood to Rotterdam. This journey took months and required craftsmanship, commercial skills and organisational talent.

“The Dutch firs were particularly sought-after,” explains Martin Spreng in front of a mighty tree trunk. “They had to be 30 to 40 metres long, knot-free and straight as a die – ideal for ship masts and rafters. ” This wood was the high-tech material of its time.

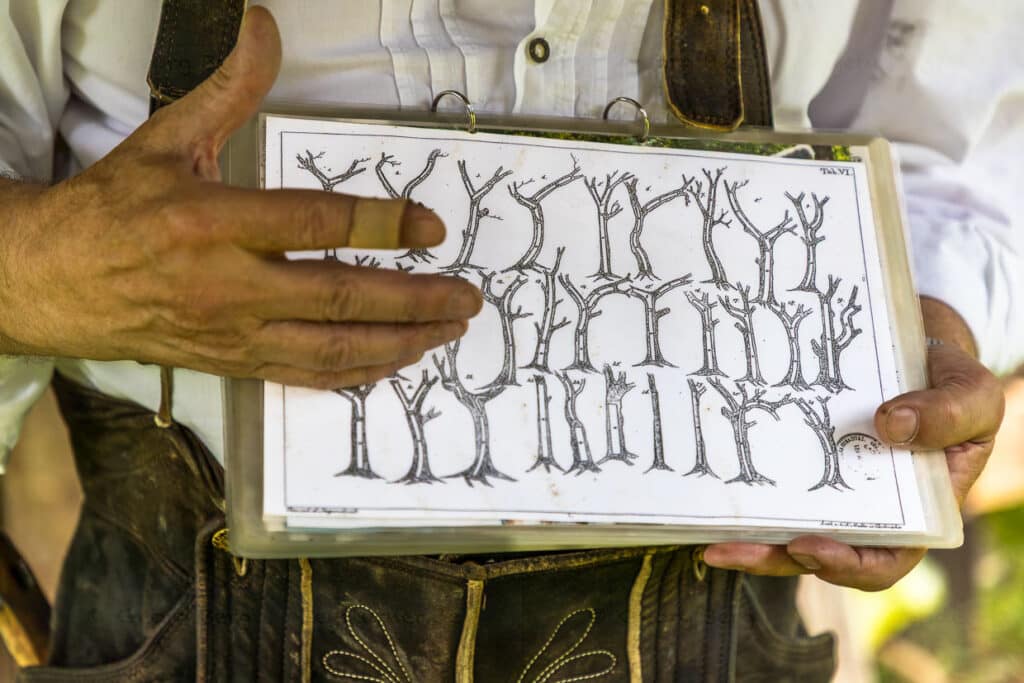

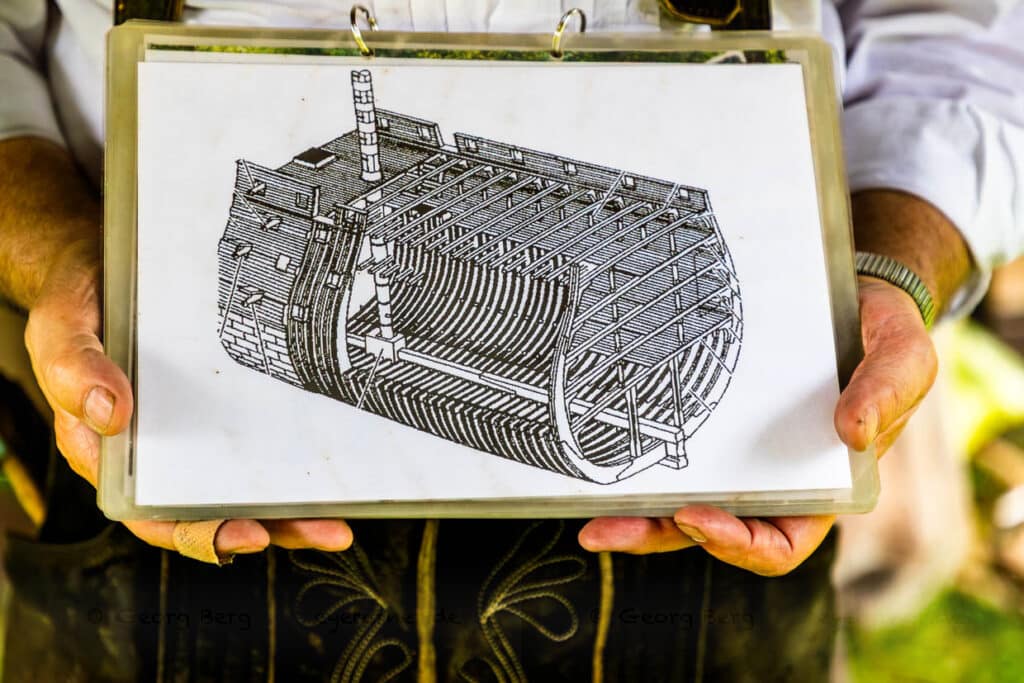

However, crooked timber also played an important role in traditional shipbuilding. With its fibres, it followed the natural curvature and was perfect for frames, which determine the shape and stability of a ship’s hull. Spreng shows us wooden templates that foresters used in the forest to select suitable trees. Crooked timber, usually oak, was up to ten times more expensive than straight timber and was also loaded onto the rafts as a load.

Raftsman Martin Sprang shows construction drawings that could be used to select trees in the forest / © Photos: Georg Berg

Water pits – the sluices of the Middle Ages

The engineering skills of the raftsmen become tangible at the Monhardter Wasserstube. These artificial basins served as both a shipyard and a lock. In the knee-deep water, labourers tied several tree trunks together to form a composite, the so-called sturgeons. They strung several sturgeons together like wagons to form rafts that were up to 286 metres long.

“When the raft was finished, we dammed up the water,” explains Spreng on the lock bridge. “Then we opened the dam with the chain winches and the raft floated to the next water reservoir, often several kilometres away. Four raftsmen could manoeuvre up to 200 solid metres of wood – the equivalent of 40 large truckloads.”

The Monhardter Wasserstube was in operation from 1640 to 1911, then fell into disrepair and was rebuilt in 1986 according to the original plans. Today, the weir system with its massive chain winches is once again fully functional.

A means of transport that consumes itself

Spreng shows us a weathered piece of beam that he found in the rubble of a demolished half-timbered house. He points to a round hole in the wood. “This is a Wieden hole. This beam was part of a raft. It was transported over hundreds of kilometres, then dismantled and used.”

A fascinating thought: the raft was not a means of transport in the traditional sense, but the cargo itself. The raftsmen turned the goods into a vehicle. “You don’t build ships that return empty,” explains Spreng. “You tie the goods together so that they carry you. At the destination, the raft is dismantled and sold.”

Wieden – the all-connecting force

“A raftsman’s life depends on the Wiede,” says Spreng, holding up one of these wooden ropes. What looks like a twisted stick was a high-tech product of its time. Wieden, made from fir or hazel wood, held the trunks, which weighed tonnes, securely together.

The production was time-consuming. Workers soaked thin logs in water for days, heated them in a baking oven and clamped them in a workbench. Using a twisting rod, they twisted the fibres until a spiral structure was created. “Waterproof, durable and superior to all other ropes,” says Spreng proudly. After the raft trip, they dried the woden and used them as torches.

Carded boots – symbol of a tough profession

Spreng wears the typical high shaft boots. “The brimmed boots are part of every raftsman’s basic equipment,” he explains. “If you’re standing in icy cold water for hours on end, you need the best boots.” The raftsmen’s equipment was well thought out, the job was dangerous. Drowning, hypothermia and crushing injuries were common. The rafting guilds maintained widow’s funds.

From systemically relevant to cultural heritage

With the expansion of the railway, rafting rapidly lost its importance in the 19th century. What was once indispensable for Europe’s economy became obsolete within a few decades. The last large raft travelled down the Nagold in 1911.

If you walk through the northern Black Forest today, you will discover traces of rafting everywhere: magnificent half-timbered houses, old weir systems, dilapidated water reservoirs. Field names such as Floßhafen or Flößersteig are reminders of the past. Books with wooden signs are stored in archives, showing how precisely rafting was organised – a logistics system with contracts, insurance and quality controls.

Today, rafting has cultural value. In 2022, UNESCO recognised it as intangible cultural heritage. Martin Spreng and colleagues from Europe campaigned for this. “That was an important moment,” says Spreng. “A recognition that this craft must be preserved.”

The Oberes Nagoldtal Rafting Guild has 30 members who maintain the Wasserstube, demonstrate the craft and build rafts themselves – most recently at the German Rafting Day in Magdeburg.

How three Black Forest traditions are connected

Large-scale deforestation for rafting left traces that went far beyond forestry. Where dense fir forests once stood, open pastures emerged—ideal for sheep farming, which developed into an important industry. At the same time, blueberry bushes spread across the cleared areas, establishing a tradition that continues to shape the Black Forest to this day. Thus, a logistics system that supplied Europe with wood led to a complete change in vegetation and created new cultural landscapes. The history of rafting, blueberry farming, and sheep farming are inextricably linked—three facets of a region in transition.

Rafting today – from Finland to Vancouver Island

Rafting lives on. “Commercial rafting is still practised in Finland and Russia,” says Spreng. On Canada’s west coast, rafts transport huge quantities of timber across the sea. Storms sometimes tear them apart and the logs are stranded on deserted coasts. Proof that this ancient principle still works in the 21st century – in places where there is no alternative.

The research trip was supported by Schwarzwald Tourismus