In mid-December, all hotels in Konya are fully booked. Street vendors offer figures of men in white skirts. Large letters are emblazoned everywhere: Şeb-i Arus. Konya, a city of two million inhabitants in Central Anatolia, lives economically from agriculture and industry. Culturally, everything revolves around Rūmī.

Rūmī’s death as a celebration

Şeb-iArus – the “wedding night” – marks the anniversary of the death of Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī, known in the West as Rumi. The Persian poet and mystic died in Konya in 1273. Every year on 17 December, thousands of pilgrims make a pilgrimage here to celebrate his death as a union with God. The highlight is the ceremony of the dervishes, members of a Sufi order, who spin in circles for hours. No dancing, no show – just a meditative practice. Devout Muslims revere Rūmī as a spiritual master and call him Mevlana.

Konya – centre of Islamic mysticism

Konya is not a pretty city. Two million people, industry, traffic. But a turquoise dome shines in the centre: the Mevlana Museum, Rūmī’s final resting place and the city’s landmark. Visitors crowd in front of the entrance. Inside, a queue pushes through a narrow corridor to see the green velvet-covered sarcophagus. Some cry, others murmur prayers.

In the courtyard are artistically inscribed gravestones, with red roses blooming in between – even in December. A young man sits in one room, engrossed in an old book. His clear voice carries Koranic verses through an amplifier into the inner courtyard of the former Dewisch monastery.

Banned and yet celebrated

In 1925, Atatürk banned the Sufi orders as part of his radical secularisation. The law is still in force today. Nevertheless, the Turkish government licences Şeb-i Arus as an intangible UNESCO cultural heritage site – officially as a “cultural event”, not as a religious practice. A contradiction that shows how Turkey deals with its Ottoman heritage: prohibit, but utilise. The pilgrims come from Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Europe and North America. Some are Muslims, many are not. Rūmī is read in more than two dozen languages, and in the USA he is considered the best-selling poet. In Konya, you can meet both: the Persian Muslim mystic of the 13th century, whose tomb is honoured in the Mevlana Museum. And the universal poet that international visitors are looking for.

From scholar to mystic

Professor Bilal Kuşpınar from the University of Konya explains Rūmī’s career: “He was a respected scholar until he met Shams al-Dīn from Tabriz, a wandering dervish. This encounter turned him into the Mevlana who is revered today. Shams taught him to achieve altered states of consciousness through dance and music. For Rūmī, Shams was a mirror in which he recognised the divine brilliance of his true self.

After Shams’ mysterious disappearance, Rūmī wrote his main work, the Mathnawi – 25,700 verses about the nature of God, love and the human soul. In addition, there is the Diwan-i Kabir with around 40,000 verses; philosophical mammoth works that are still read today.

The Sema – meditation in motion

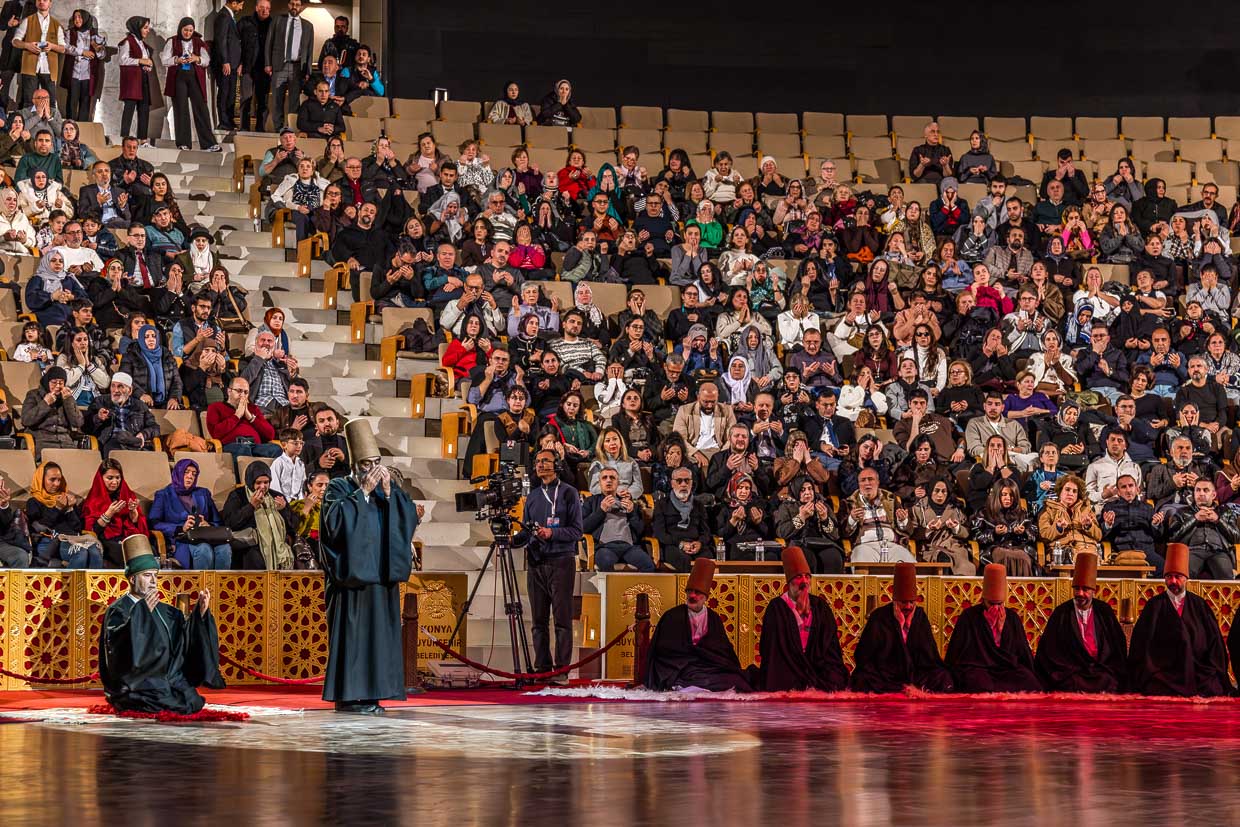

On the evening of 17 December, the Mevlana Kültür Merkezi fills up. 3,000 seats, colourful lighting, cameras from Turkish television. What follows is not a folklore show, but a religious ceremony that has to be declared a “cultural event” in order to circumvent the 1925 ban. The dervishes do not spin for the audience, but for themselves.

The ney, a reed flute, sets the tone. Its plaintive tone symbolises the longing of the soul, which is separated from God. The kudüm, a small kettle drum, gives the signal for the beginning with a single beat.

What began in 1244 as an encounter between Rūmī and Shams became a permanent choreography after Rūmī’s death. Shams, a man without formal education, taught Rūmī not theology, but trance dance, fasting and meditation. The difference between knowledge and experience. Rūmī’s descendants systematised these practices into sema – a ceremony with set movements, music and symbolism. What began as a personal spiritual quest is now a precise ritual. Dervishes see themselves primarily as practitioners – some are also scholars.

The sema is meditation in motion. The sikke, a high felt hat, symbolises the gravestone, the tennure, a white skirt, the shroud, the hırka, a black cloak, the grave. The removal of the cloak symbolises the transition from death to life. In the whirling dance, the right hand points upwards, the left downwards – the dervish as a channel between heaven and earth. They turn anti-clockwise, in some interpretations this is symbolically directed against the ego. The right foot remains fixed, the left foot drives the rotation.

Three days ago, I couldn’t have told you what a dervish was. Now I’m sitting in a packed hall and see people spinning – for 30, 40 minutes without interruption. Whether they feel God or fall into a neurologically explainable trance, I don’t know. But I do understand why people from all over the world come here: They are looking for an experience that cannot be put into words. Konya thrives on this contradiction – a conservative city that worships a radical mystic. A forbidden order that is celebrated as cultural heritage. A religious practice that has to be sold as a show in order to remain legal. Rūmī would probably have smiled at these contrasts. He who wrote: “Religions are like lamps, but the light is the same.”

Tickets for the Şeb-i Arus events sell out quickly. It is therefore advisable to book in good time.

The research was supported by GoTürkiye