It hisses, bubbles and steams. Lake Laugarvatn, an hour’s drive from Iceland’s capital Reykjavik, is one of those places where you learn how Icelanders use their often archaic nature. In this case, not for swimming or heating frozen sidewalks, but for baking bread. Rúgbrauð is a dark, long-cooked rye bread similar to German pumpernickel, only sweeter.

You can get Rúgbrauð in any supermarket in Iceland. But then it is conventionally cooked in an oven. Hverabrauð is when the bread dough is baked in the ground and with the energy of a hot spring. The heat during the long baking process causes the sugar to caramelize. This makes Hverabrauð almost irresistible when it is dug out again after 24 hours. However, you should curb your appetite a bit. As delicious as the bread tastes, it is heavy on the stomach and causes turbulence in the intestines. This has earned it another name. It’s also called thunder bread.

Geothermal energy – energy at zero cost

While energy prices are skyrocketing all over the world, Icelanders have been harnessing the energy of hot springs since their settlement in the 7th and 8th centuries AD. Settlements sprang up near them early on. To this day, geothermal energy is one of the country’s most important sources of energy. In many places, the groundwater in Iceland is so close to magma chambers that it is extremely hot and is used to generate energy. Records from the 12th century show that the hot springs were used for cooking even back then. This was also a matter of conserving resources. This meant that the settlers did not have to burn either the scarce wood or the valuable peat. Baking the typical rye bread Hverabrauð at a hot spring can be experienced during a trip to Iceland near Reykjavik and in the northeast at Lake Myvatn.

Laugarvatn Fontana Bakery at the Golden Circle

Steam is rising from Lake Laugarvatn. A large black and yellow sign warns of the high temperatures. Countless hot springs in the water or directly on the lakeshore bubble and hiss. Here, where the North American and Euro-Asian plates meet, there are especially many of them. Sigurdur Rafn Hilmarsson is a native of Laugarvatn. His grandmother and mother used to bake hverabrauð in the bubbling places by the lake. His family can trace this custom back to the 18th century. Siggi Hilmarsson was born in Laugarvatn, a village of 200 people. He has seen the number of tourists in Iceland increase year by year. Between 2010 and 2018, the number of tourists increased fivefold. In Laugarvatn, they knew how to take advantage of the prominent location on the Golden Circle.

Iceland’s natural wonders lie like a string of pearls along the 230-kilometer panoramic route. If you are coming from Reykjavik and want to see Geysir, the namesake of all geysers, and the thundering waterfall Gulfoss, you will also pass Laugarvatn. Siggi Hilmarsson is the idea man and today’s manager of Laugarvatn Fontana. The original attraction of Laugarvatn was the geothermal bath. In the 1920s, a bathhouse stood in the same spot on the lake. Today it is a chic wellness oasis.

Hilmarsson, a trained chef, noticed that besides bathing, baking is also very popular with tourists when he made a notice in Laugarvatn’s hotel a few years ago offering to accompany him to the hot springs to bake bread. The next morning there were 80 people at the reception. A week later, the first tour operator came knocking and the success story of the Laugarvatn Bakery took its course. Even in the low season, Laugarvatn Bakery offers a baking demonstration twice a day followed by a tasting. During the high season in summer, there are even three dates.

In rubber boots to the oven

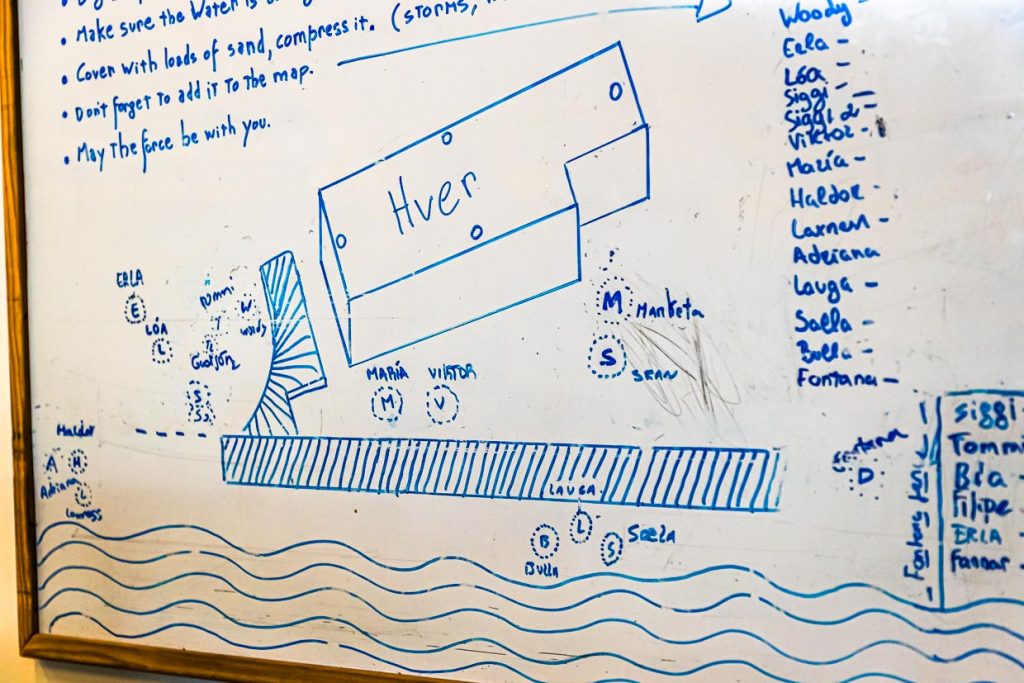

The bread event in Laugarvatn is so popular that there is a site map that looks a bit like a treasure map. The baking places are called Maria, Viktor or Erla. The Fontana Bakery team has to note when they buried a bread pot where, so that the next shift knows which hot spot to lift a baked-out loaf. Beatrice, in rubber boots and rain jacket, grabs a shovel. In the other hand she carries a pot wrapped in foil. The baking pan with a lid is half-filled with bread dough made from the ingredients rye flour, yeast, milk, water, salt and sugar. She leads the group to a small earthen cone called Sean. The stone at the top indicates that this place is occupied by a loaf of bread. The shore with the hot baking places is still available to all the inhabitants of Laugarvatn, she tells. Even her grandmother used to bake bread here.

With well-aimed spade stabs, she uncovers the baking hole. The bread pot is hot and full of soil. Therefore, it first gets a shower in the lake. This removes the dirt and cools the metal. The foil protects against water penetration both in the baking hole and during cleaning in the lake. Still outside at the hot spring, Beatrice opens the pot and shows everyone the dark brown, slightly domed top of the bread. After 24 hours in the hot earth, the rye bread is baked in its own moisture.

Before we start tasting, we have to bury the new bread in one of the hot holes. Beatrice places the fresh baking pan in the hole and shovels some of the hot water over the pot. Immediately, hotter water rises from below. Sometimes, when it rains a lot and the water in the lake rises, the hot springs are flooded. Then the breads become undercooked because the temperature in the baking hole drops. In addition, the holes migrate, Beatrice explains. The hottest spot is not always in the exact same place. An indicator of a perfect baking hole is silver specks in the sand and steam rising from small holes.

Back in the foyer of the geothermal bath, the bread is tumbled out of the mold, quartered with a long knife and cut into thin slices. Beatrice explains that Icelanders like to eat their Rúgbrauð with lots of butter. Something more noble is the combination with smoked trout. At Laugarvatn, the trout come from the lake. The rye bread is still lukewarm and tastes delicious, as mentioned at the beginning. Especially in combination with the smoked fish.

The recipe for Hverabrauð comes from the grandmother of manager Siggi Hilmarson. It is not a well-kept family secret, anyone can take it and try their luck. But without a hot spring to give the bread that special caramel note, the baking result is unlikely to match the original from Laugarvatn. If you still want to try, here is the recipe. For the Black Sand rye bread, Fontana Bakery uses: 5 cups of rye flour, 2 cups of flour, 2 cups of sugar, 4 teaspoons of baking powder, 1 teaspoon of salt, 1 liter of milk and 250 ml of water. “Verði þér að góðu”.

Baking and bathing

At this stop on the Golden Circle you can combine bathing in hot springs with the culinary attraction of Rúgbrauð with trout. After all, Lake Laugarvatn is not just for cooling hot bread pans! Bathing is possible all year round at Laugarvatn Fontana Geothermal Baths and Bakery. Baking, on the other hand, only from the beginning of June to the end of September. Also interesting is another look under the earth’s crust. In Reykjavik, water from the hot springs is used to heat the sidewalks . Another delicacy of the country is hakarl, the somewhat stern-tasting meat of the Greenland shark. If you don’t want to eat animals but want to look at them, you should know how people in Iceland feel about horses and why only there are the smart leader sheep.