“Mon Dieu” – let’s face it – many things just sound better in French, more elegant, downright mysterious and slightly wicked. Absinthe, in German Absinth is such a word. This name carries the taste of the forbidden. Somehow everyone has heard of it. Details are often unknown. Yet it is worth taking a look at the eventful history of this drink, which translated into German simply means wormwood and conjures up associations with a herbal bitters from grandpa’s cellar bar. But with absinthe, it’s different.

The green fairy and the bitter truth

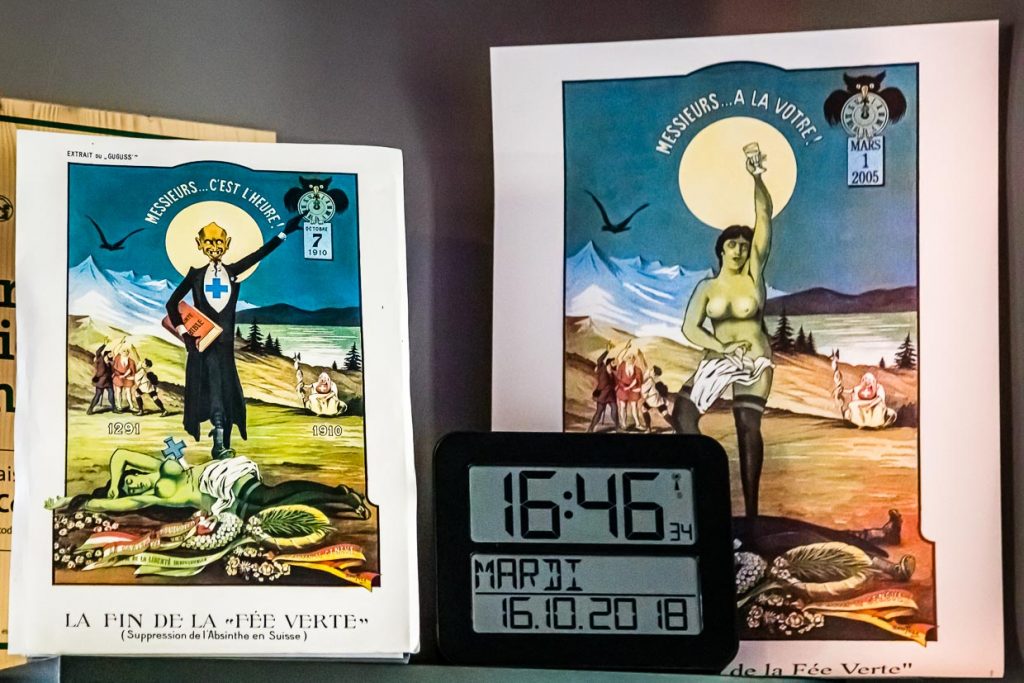

Absinthe was surrounded by great names of the Belle Epoche, Picasso, van Gogh and Hemingway, among many others. Later, the seductive green drink with the slowly dripping cold spring and the decorated sugar spoon became a prop typical of the epoch in motion pictures such as Bram Stroker’s Dracula. In addition, a 96-year ban in France, the country where absinthe celebrated its greatest sales successes. A host of conspiracy theories, which have since been scientifically refuted, including a family tragedy in 1905 that was exploited by the media and, like a modern-day shitstorm, dealt absinthe its death blow, leading to its prohibition in Switzerland in 1910 and in France from 1915.

Route de l’Absinthe from Pontarlier to the Val de Travers

All the exciting details surrounding absinthe can now be traced with pleasure during leisure time. The regions that once competed in absinthe production have worked out a common route, along the route of which lie historical sites, but also distilleries that are still active today.

We visit the Maison de l’Absinthe in Motiers, in the Val de Travers. It was in this valley that absinthe was invented in its blend of wormwood, anise and fennel and, depending on the recipe, other herbs such as hyssop or lemon balm. In 1797, the first commercial distillery was established here. Today, a museum recalls the eventful history of absinthe. The breakthrough, however, is due to the numerous distilleries in Pontarlier, France. Enormous quantities were produced there until it was banned in 1915.

Absinthe – in ancient times it was considered a remedy

The transformation of absinthe from a remedy to an evil and wicked herb is curious. Since ancient times, the great wormwood is considered a jack-of-all-trades in the art of healing. Even then, wormwood was added to wine. Its therapeutic effect covered a wide spectrum: from a proven sleep aid, remedy for stomach complaints, rheumatism, seasickness and gout. Yes even with hair loss and worms in the ears, it is said to provide relief.

The success of absinthe, the belle époque and the green hour

Absinthe became fashionable through the French soldiers in the colonial territories. Military doctors mixed absinthe into their soldiers’ often contaminated drinking water to render pathogens harmless. Those returning home continued this habit. Absinthe was consumed in the early evening hours starting at five o’clock.

The artists of the Belle Epoche took up this drinking ritual, celebrated it and immortalized absinthe in their paintings and stories. From today’s perspective, it seems as if the entire elite of the European art scene staggered through the Paris of the late 19th and early 20th centuries intoxicated by absinthe. Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh were among the well-known absinthe drinkers. Manet, Degas and Baudelaire literally incorporated absinthe into their art as well. Gauguin and Picasso often chose the motif of the absinthe drinker. Absinthe was the first drink that women who did not belong to the demimonde could drink in public. The herbal bitters were far less expensive than wine. The slow dilution with water from the cold spring could be drawn out over hours. A welcome reason to linger longer in the bars rather than return to cramped quarters in a big city like Paris. At the beginning of the 20th century, Paris therefore had an unheard-of density of bars and cafes.

The taste of the forbidden – the end of absinthe

The abrupt end came between 1907 and 1923 in almost all of Europe. Too many alleged absinthe addicts, a decline in morals and a good lobbying by the winemakers, who lost more and more customers to absinthe, as well as a family drama with a fatal outcome, created a negative mood on a broad level. Prohibition could no longer be stopped. But still, absinthe survived in Switzerland through moonshine distilling. In France, distilleries shifted to the production of pastis. The most famous brand became Pernod.

Absinthe – production in times of prohibition

Especially in the Val de Travers, the moonshine distillery flourished. Everyone in town knew what it meant when the smell of anise drifted through the street. But the law of secrecy applied. In the evening hours, the absinthe couriers went from house to house, refilling their customers’ supply bottles. Under their long coats they wore hip flasks with a large capacity, adapted to the shape of their bodies.

About 80 years after the ban, absinthe was allowed again in the EU – regulated. Since then, absinthe has been steadily gaining popularity again. Today it is available in a wide variety of qualities, colors and alcohol concentrations. It is very interesting that some manufacturers, Absinthe after own, old prescriptions again manufacture. It can be assumed that these products are not fundamentally different from the products of the 19th century.

Absinthe – victim of its own success

Between 1907 and 1923, absinthe was banned in just about every European country. In Pontarlier, the stronghold of production, people shifted to making pastis based on anise. The use of wormwood was prohibited. This was because the essential oil thujone contained in wormwood was blamed for harmful effects such as dizziness, hallucinations and mental and physical deterioration. Today it is scientifically proven that the many damages are rather due to the consumption of too much and too bad alcohol. Even the thujone content of the historical absinthe is said never to have been a health hazard. Rather, it was mainly the successful lobbying of the winegrowers that led to the prohibition of absinthe, as they were the losers in the absinthe boom. Because the herbal bitters were cheaper than wine.

The balance of bitterness and sweetness

The cold spring – the very cold water drips onto the sugar cube and through the richly decorated spoon into the glass with the room temperature alcohol. The wormwood turns a milky green color. This effect gives its name to the green hour. From five o’clock in the afternoon was the meeting point in the bars.

The play of the cold spring, the tall glasses, the spoon, the discreet dosage made absinthe also a drink of the ladies. A well-dosed intoxication in times of the blossoming art nouveau. A ritual mystical and spiritual, which was played late into the night. It was transported further into society via the art scene and the first cinema films.

Absinthe in cocktails and dishes – bitter triumphs

Bitter vegetables such as cabbage and chicory are on the rise, and coffee and even tea consumption are on the rise worldwide. And vermouth, the seasoning bitters Angostura and absinthe are also playing an increasingly important role in the bar scene. The world is getting bitter! This trend has long since arrived in top gastronomy. Tart flavors mime the perfect counterpart to sweet. Bitter components strengthen the immune system and prolong the feeling of satiety. That sounds suspiciously like a superfood. In the kitchen, absinthe is ideal for flavoring stewed cocktail tomatoes, for example, or for deglazing meat that has just been fried.

Since absinthe has been scientifically proven free of the suspicion of a hallucinogenic effect, nothing stands in the way of its renaissance. If only Oscar Wilde had known that back then! For him, absinthe was an almost poetic drink. But from Oscar Wilde also comes the quote: “After the first glass, you see things as you would like to see them … In the end, you see things as they are, and that is the most horrible thing that can happen.”

Travel information

The Route of Absinthe

On foot along the Route de l’Absinthe

The Absinthe Museum in Motiers

Maison de l’Absinthe

Print publication

The crime scene: moonshine distillery, Transhelvetica #60.20, Aug. Sep. 2020, p. 92.

The research trip was partially supported on site by the French Tourism Federation