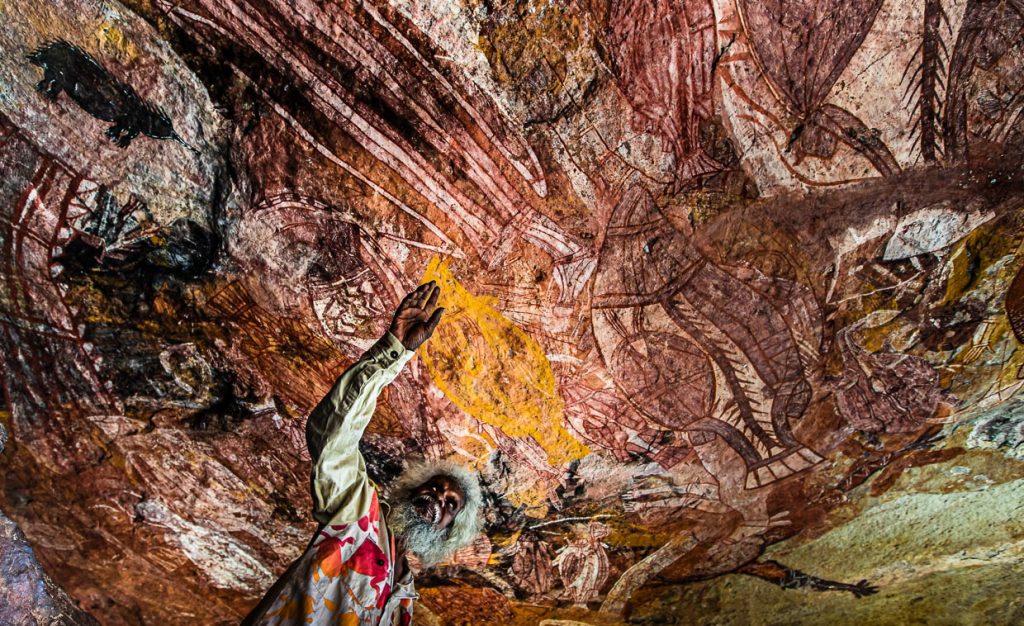

The rock paintings of the Australian outback are works of the oldest continuous art tradition in the world. Many galleries in northern Australia are still well preserved despite being exposed to the elements for 20,000 years. They create a sense of awestruck wonder among both Aborigines, as Australia’s indigenous people are known, and international visitors. And this despite the fact that they cannot be subordinated to any European-influenced concept of art.

But first things first. Part of the nature of rock paintings is that they can only be experienced in their own place. These sites are remote and elude curatorial treatment. Some are so sacred that not everyone is allowed to go there. This restriction even applies to most Aboriginal people. This is because there are numerous tribes, each with their own language and cultural space. The rock galleries belong to the tradition of the tribes living there and shape their identity in the respective areas. They are not to be understood merely as works with which an artist expresses himself. Some drawings are even believed to have been created by spirits.

The reverse concept of ownership

In Australia, Aborigines living in their original tribal areas are called Traditional Owners. This choice of words is admittedly intended to show them the respect today that was denied them for a long time with British colonization. The concept of ownership, however, misses the core of the Traditional Own ers’ self-image. For in the deeply rooted attitude of the Aborigines, there can be no ownership of land. It is even the other way round: The inhabitants belong to the land and their life is essentially shaped by it. This attitude, which is difficult for white culture to understand, is still fraught with tension in today’s Australia.

Access by escort only

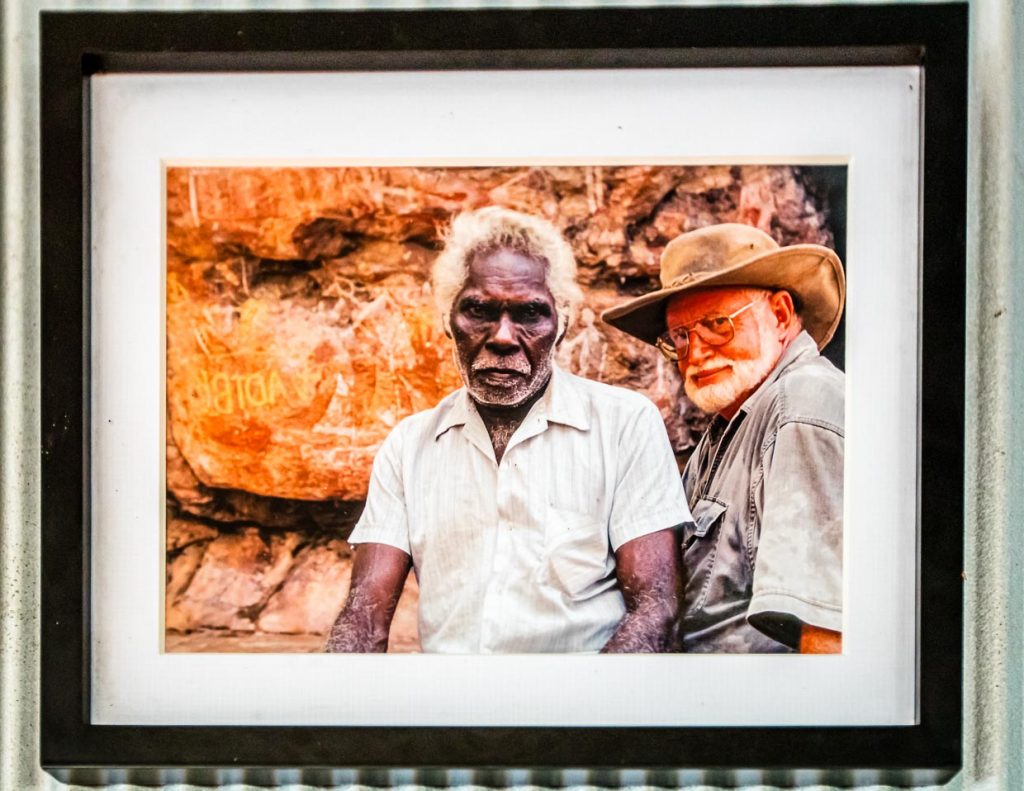

Guided by Sab Lord, our small group hiked for days through the hot steppe on the ancient dream trails until we reached – each time surprised again – another of the ancient galleries.

Sab Lord has the typical rough-legged manner of the white pioneers. Therefore he sets narrow limits for us tourists from the beginning and there is a reason for that. All rock galleries are located in areas where you are not allowed to enter without a permit and without guides approved for this purpose. This and also the long distances have certainly contributed to the fact that there has not yet been any significant vandalism. We have seen that hand axes or grinding tools for extracting the precious color pigments have been lying ready for free use in rock niches for centuries. It is this reality that poses a special challenge for guides like Sab Lord. After all, he enjoys the trust of the Traditional Owners only as long as the tourists he guides respectfully enter the cultic places of the Aborigines and leave them in their original state. He meticulously makes sure that nothing is stolen, no walls are touched and no photos are taken of bones that have been laid openly in rock crevices for their final resting place.

“Blackfellas” they call themselves

Sab Lord is very familiar with the Aboriginal way of life, having spent his childhood as a Whitefella (white fellow) in the outback on his parents’ buffalo farm together with Blackfellas of the same age. Regardless of tribal affiliation, these terms are not perceived pejoratively.

Fundamental misconceptions

The way of life of the Blackfellas meets with a lot of misunderstanding in the westernized everyday life. In order that our readers do not prematurely condemn the outward appearances that catch the eye, there are no pictures of the housing estate at Sab Lord’s request. The houses are built according to all the rules of Australian craftsmanship. But since Aborigines live mainly in the open air, the houses serve more as storage rooms and do not look very appealing to us.

The magic of the rock paintings is hard to put into words

The art in Arnhemland is so fascinating that for a long time I could not find an adequate way to describe it. The magic that the rock paintings have exerted on me is still difficult to put into words. No wonder, because to this day they serve the Aborigines as a support for the oral tradition.

In this context I should mention my travel companions Katja Bockwinkel, Rainer Heubeck and Cornelius Pollmer. Certainly, each of us remembered different aspects. But the common attempts to understand what we saw and the memory of the amazement of the others let me bear my own continuing lack of understanding more easily.

Stories are told in detail

Thommo, the local guide, has interestingly brought Sab Lord closer to us by not coming along himself. We climb up into a rock massif that is called Long Tom Dreaming in English. At first, almost shyly, Thommo tells the ancient stories and we feel very closely how oral tradition works. The detailed stories are mainly about the motives of the depicted figures, which thus become alive and do not need to be described in detail.

Sab has previously given us as the only advice on the way to repeat each question at most twice. If then still no answer comes, it will probably not be because of the linguistic understanding, but because of the secrets, which no stranger is allowed to know.

Portrait: Sab Lord, the Australian outback legend

Travel advice: Australia for European tourists